The Creation of the World Indigenous Spiritual Biosphere Area (WISBA)

How First Nations governments in Canada can help protect the last remaining pristine biospheres of the planet, and collaborate with indigenous communities of the south in the spirit of cultural revitalization

Updated - December 24, 2023

In early 2022, I embarked on a 38-day solo motorcycle trip through the Maya world. Beginning as far East as I could go, I started my journey on a sunrise at the eastern shore of Cozumel. From the tranquil Caribbean island I made my way south to the small beach village of Mahahual. Once a humble fishing village, the town’s existence is now sustained by the 3 cruise shops that dock at the city every 2 days during the tourist season. From there I traversed south past Tulum, the “Spiritual Las Vegas of Mexico” where cartel-controlled bars have been replaced by cartel-controlled Ayahuasca circles, and skimmed through the ever shrinking jungle around Bacalar, a small town surrounded by a once-federally protected area now home to the biggest real estate boom in all of Mexico. Flying past these “Pueblos Mágicos” of the Yucatan, I instead camped at the ‘Biosfera de Calakmul’ (Calakmul Biosphere) in the Campeche state of Mexico. After sleeping 9-nights underneath the scorching sounds of the howler monkeys, I trekked even more inwards to the saturated mountainous regions of Chiapas, the southern most state of Mexico. The city of Palenque, another “Pueblo Mágico”, sits in the northwestern edge of the La Selva de Lacantun (Lacantun Jungle), considered the birthplace of the great Maya Civilization. From there, I crisscrossed underneath the jungle canopies and cliffs and circumnavigated the 331,320 hectare Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. Afterward being in presence with the most beautiful waterfalls I had ever seen, I travelled north, passing through the city of Comitan and ending my trip in the Zapatista stronghold of San Cristobal de Las Casas. In Mexico, I learned that Time Among the Maya moves fast with a slow burn. Cafe sips and hammock naps occur feet away from the 24-hour cycle of raising a hotel from scratch.

Along the way I interacted with many people from all over the world, many indigenous peoples, who were always open for friendly conversation. However, there was stark contrast in the way a certain group of people acted, towards everybody. Usually the women, dressed in a full dress that looked straight out of a western TV series, were carrying very long faces, never smiled, and were either sitting in vehicles, following men, or sitting behind their fruit table at a local market. The older men walked with their chests out, often followed by very dark-skinned Mayas — If no women were around, the Mayans were always driving. I began asking who were these mysterious people who kept to themselves, and whose houses and neighbourhoods I hadn’t yet seen.

CHAPTER 1: THE GREAT SPIRITUAL MIGRATION

Mennonites

Believe it or not, a modern photo of young Mennonites. Photo from Google

50 years ago, Mexico's National Tourism Development Fund unveiled Cancún, their first mega-project, which was marketed as "the new thousand-year-old world on the Mexican Caribbean." At that time, the Yucatan was the least-populated state in the country, filled mostly with virgin forests and swampy conditions and considered to have no economic viability. Today, Cancún Airport receives more international flights than any other Mexican city, including Mexico City, one of the largest cities on planet Earth. Cancún's success inspired similar efforts in Playa del Carmen, Cozumel, and Tulum, proving that tourism, also known as "the industry without chimneys," could diversify Mexico's economy. However, the rapid influx of tourists and workers raises the question of who will provide food for them.

The Mennonites are a religious group that traces its roots back to the Radical Reformation of the 16th century in Europe, named after Menno Simons, a Dutch Catholic priest who became a leader of the Anabaptist movement. The Mennonites who live in the Yucatan region of Mexico are descendants of a group of Mennonites who originally settled in Canada. In the early 20th century, these Mennonites were living in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, but they had trouble with the Canadian government over their refusal to send their children to public schools, which conflicted with their Christian religious beliefs. Elder Heinrich H. Janzen led a group of Mennonites in search of a new home where they could live according to their beliefs, eventually settling in the Yucatan region of Mexico in 1948. The Mexican government was open to allowing the Mennonites to settle in the Yucatan because they saw them as a way to bring "modern" agriculture techniques to the region and feed the entire 'Mundo Maya' (Maya World) megaproject.

The first Mennonite families arrived in the Yucatan in 1948 and settled in the town of El Sabinal. They quickly discovered they could subvert the Mexican ejido system, a communal land ownership policy enacted in response to the 1917 Mexican Revolution, by deceptively marrying local young Maya women only to divorce or disappear them after they received the rights to their land. By having enough men become part of local indigenous communities through the subversion of the ejido system, the Mennonites could kick out the original Maya inhabitants from the decision-making process and even create their own communities in new regions. Today, around 15,000 Mennonites continue to live according to their Manifest Destiny-like traditional beliefs and practices, while some of their communities have been accused of illegally acquiring and occupying land, using unsustainable agricultural practices that damage the environment, and being insular and resisting integration with broader Mexican society. Reports of child abuse and domestic violence within Mennonite communities have also surfaced. An eye-opening exposé by environmental journalists at Mongabay reveals the severe deforestation solely attributed to the Mennonite communities in the Yucatan. Their farming practices are depleting groundwater resources, polluting rivers and streams, and harming local ecosystems.

Especially after the global totalitarian measures to curb the COVID-19 virus, a new-generation of migration has begun.

CHAPTER 1: THE GREAT SPIRITUAL MIGRATION

Tuluminati

The spiritual humility of the “Tuluminati”, a self-proclaimed description of many new expat residents of the city in the Yucatan state of Mexico. Photo from Google

The steady stream of Canadians, Europeans, and Americans is what has quenched the thirst of the tourism since the 70s. Now, the water that has arrived has changed taste; what Mexico provided for foreigners was mostly alcohol and sun, and now it is spiritual awakening… and sun.

The assimilation of psychedelic plant medicines and their ceremonies in places like Tulum has been gaining increasing attention in recent years. These practices have been used by indigenous communities for thousands of years as a means of connecting with our expanded consciousness, nature, and the spirit world. However, with the rise of modern psychedelic culture and the spread of information through the internet, these ceremonies have become more accessible to a wider range of people—and when an idea becomes mainstream, only the superficial aspect becomes understood. This is the nature of an idea becoming popular.

Mexico is the Central American hotbed for young, impressionable, and messianic voyagers to descend upon and unknowingly take part in assimilating and destroying the Indigenous cultures they so revere.

One of the most commonly assimilated plant medicines in these ceremonies is Ayahuasca, a sacred brew made from the two or more different plants. Ayahuasca ceremonies are typically led by trained shamanic practitioners who guide participants through a process of introspection and self-discovery. These Ayahuasceros often come from medicine families and a student must learn under his or her teacher for at least 30 years to be taken seriously as a true cosmic healer.

Another plant medicine commonly used in these ceremonies is Psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. Psilocybin ceremonies are similar to Ayahuasca ceremonies, with participants consuming the mushrooms under the guidance of a trained facilitator. These ceremonies can also be intense, with participants experiencing profound changes in their perception and emotional state.

Not only do most people who take these plant medicines in Mexico never commit to integrating their experiences with a practiced routine or comittment to helping the indigenous communities where the traditional medicines have been kept alive, they also live in a bubble where they do not want to be around “bad vibes”. This means that when large-scale megaprojects are tearing down the jungle or illegal logging activity is occurring nearby, or cartel organizations peddle more psychedelic trafficking, it is best to stay in the circle and choose not to face the sometimes grim realities most indigenous peoples face.

Of course, this isn’t the case for many people and communities who are ingesting and using psychedelic plant medicines for healing. I am only highlighting the most grotesque use of the technologies to showcase what occurs when the current, popular non-indigenous consciousness is adopting such experiences.

Flying past these pueblos mágicos of the Yucatan, I camped at the ‘Biosfera de Calakmul’ (Calakmul Biosphere) in the Campeche state of Mexico. After sleeping eight nights underneath the scorching sounds of the howler monkeys, I met up with representatives of the ‘Consejo Regional Indigena y Popular de Xpujil’ (Indigenous and Popular Regional Council of Xpujil). This small cafe-sized office represents up to 14 Indigenous Maya communities throughout the Campeche state. The organization is the loudest opposition to the Mexican Government’s $15 billion ‘El Maya Tren’.

The Maya Train, in English, project is a large infrastructure project in Mexico that involves the construction of a railway network in the Yucatan Peninsula. The railway will cover 1,470 km (910 mi) and connect major tourist destinations such as Cancun, Tulum, and Palenque. This means tourists can party in Cancun on Friday and walk in a deep-jungle tour in the Calakmul archeological site on Saturday.

In 2021, CRIPX temporarily stopped the $15 billion project’s construction within the Calakamul sector of the proposed route. Because of this, representatives received death threats from the locals of Xpujil, who are anticipating a similar economic explosion as Tulum, Bacalar, and Palenque. Because of such strong resistance against the train’s route through the jungle, the Mexican Government hired the Army to construct the Calakmul leg of the route. Unfortunately, the construction of the Calakmul route has continued.

The opening of ‘El Tren Maya’ ‘The Maya Train’ will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the second-last remaining rainforest biosphere in Mexico, which is also one of the largest in all of Central America. As someone who has had the privilege of camping in the biosphere and driving through the breathtaking one-hour journey under the dense jungle canopy to the archaeological site, I can attest to the beauty and fragility of the ecosystem. However, the construction of the train project will lead to the expansion of the road network, which may bring in larger trucks that will cut down more of the jungle. During my trips, I counted 48 turnoffs from the main road that lead to small fields growing crops sold in Xpujil and surrounding communities. Unfortunately, the train project may bring in more infrastructure that may increase the rate of deforestation. It's essential to consider the long-term impact of the project and ensure that sustainable measures are put in place to protect the delicate ecosystem for future generations.

I ventured deeper into the saturated mountainous regions of Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico. It’s here where another ‘pueblo magico’ exists. Palenque, is situated on the northwestern edge of the La Selva de Lacantun (Lacantun Jungle), considered the birthplace of the great Maya Civilization. I ventured beneath the jungle canopies and cliffs, circumnavigating the 331,320-hectare Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, which is one of the largest remaining jungles in all of Central America. After I marveled at the stunning waterfalls, I continued my journey northward, passing through the city of Comitan, until I reached the Zapatista stronghold of San Cristobal de Las Casas, where my trip concluded.

Ending my trip in the epicentre of indigenous resistance towards the neo-liberal philosophy felt right.

What’s happening in Mexico is now happening in the Amazon Rainforest. By the same playbook, Mennonites are creating colonies in a breathtaking pace, where they are clearing virgin rainforest, spraying Monsanto products, and waiting for the residential and tourist development around them to grow.

CHAPTER 1: THE GREAT SPIRITUAL MIGRATION

The Race for The Amazon

Not only are Mennonites, Digital Nomads, and Psychedelics Dreamers all flying into one of the last remaining pristine bioregions of the planet, Global Investors are waiting at the window, adjusting their ties and inhaling their strawberry vapes.

With the creation of the $19-billion USD [first phase budget] ‘Amazon Sacred Headwaters Initiative’ (ASHI) investment white paper, the goal is now clear; who is trying to control the policies of the great Amazon bioregion? The initiative plans to “Develop a system of biophysical indicators to measure and evaluate Buen Vivir,” which means creating a technological system in attempt to quantify the spiritual system and health of the rainforest; “2.2. Promote the creation of an electronic currency in the bioregion,” which would, of course, be tied to an accompanied digital ID system. Other aspects include to “Promote a new international property system and the construction of a proposal to liberalize patents related to public health, energy efficiency technologies, renewable energies,” and “the construction of life plans to ensure legitimate indigenous governance. The main actions are: the participatory preparation and implementation of life plans for nationalities and peoples, that include representative indicators for indigenous people’s worldviews and living conditions.”’

The ASHI first-phase budget is a $19 billion USD investment, with the hopes of creating “new, functional global citizens” and keeping the last rainforests protected and conserved. But, why so much money? Where is the return on the investment?

Simplified concept of “Carbon Credit” offset invention

A carbon offset is “a reduction or removal of emissions of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases in order to compensate for emissions made elsewhere. A carbon credit or offset credit is a transferable financial instrument, that is a derivative of an underlying commodity.” In this new future marketplace, entire watersheds, forests, and bioregions will become commodities exchangeable on the global marketplace.

If the carbon credit offset initiative gains traction in the world marketplace, the Amazon Rainforest will be the largest income-generating asset in human history; the largest carbon-sink where multi-national corporations can invest in to continue their monopolistic expansion.

The next question is, “how will these commodities be measurable?” How exactly will we know how much 50 square kilometers of the virgin rainforest and its inhabitants can sequester carbon dioxide? New measurements, based upon new technological advancements, to quantify more information, will have to be created to set even playing fields for the new global commodities marketplace. This means what has usually been a spiritual relationship, will now have its turn to become “measurable information”. We will have expanded our capitalistic endeavours to include entire bioregions of the planet becoming commodified.

CHAPTER 2: BILLIONDIGENOUS

Indigenous Megaprojects in Canada

The Squamish Nation announcing a multi-million dollar project. Photo from Google

The colonization that has occurred in Canada has created one of the most polarizing standards of living in any indigenous society in the world. The World Health Organization's investigation into health determinants now recognizes European colonization as a common and fundamental underlying determinant of First Nations health issues in Canada. There have been strides made on the part of many First Nations communities to improve education around health issues. Still, despite these improvements, Indigenous people remain at higher risk for illness and earlier death non-Indigenous people. Chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are on the increase. There are definite links between income, social factors, and health. There is a higher rate of respiratory problems and other infectious diseases among Indigenous children than among non-Indigenous children - inadequate housing and crowded living conditions are contributing factors.

The very creation of the North West Mounted Police and Royal Canadian Mounted Police were to quell the Indigenous backlash towards British Crown policies. These creations have led to the inevitable situation currently occurring in Canada; 32% of federal inmates identify as Indigenous, despite only making up around 5% of the total population in Canada. Indigenous women now account for almost half of the female inmate population in federally run prisons: “On April 28, 2022, the number of incarcerated Indigenous women reached 50% for the first time (298 Indigenous and 298 non-Indigenous women in federal custody) ... this over-representation is largely the result of systemic bias and racism, including discriminatory risk assessment tools, ineffective case management, and bureaucratic delay and inertia.”

Indigenous people in Canada have some of the highest suicide rates in the world. Suicide and self-inflicted injuries are the leading causes of death for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years of age. For Inuit, the suicide rate is nine times the national rate; for First Nations, the suicide rate is three times the national average; and for Métis, the suicide rate is twice the national average. "Suicide States of Emergencies" are a tragic regular headline in Canadian news outlets; in May 2021, Shamattawa First Nation declared a state of emergency, Sioux Valley Dakota Nation declared an emergency in October 2020, and most recently, Red Sucker Lake First Nation called for a suicide crisis team in 2022. The most infamous case of suicide states of emergencies occurred in 2016 in the community of Attawapiskat, where 28 people tried to commit suicide in a single month.

On the other end of the spectrum, an unprecedented amount of wealth is about to fall into the bank accounts of many First Nations governments in Canada.

On an individual level, First Nations people in Canada account for the highest number of Indigenous millionaires in the world. On a communal level, First Nations communities in Canada in 2021 received upwards of $18 billion ($18,000,000,000) in federal funding, a 300% increase from the previous year. Whether that money is competently spent or whether it is long overdue is another story. The fact is, we are looking at the First Nations situation in Canada with an international lens.

Not only has $18 billion been given to First Nations in Canada from a federal government level, but Indigenous entities across Canada are now accounting for hundred million and billion-dollar projects and portfolios.

Fort MacKay in Alberta is one of the wealthiest First Nations communities in Canada with an annual average income of $78,916, well above the provincial average of $62,778. What is important to note is that 84% of the community's income comes from employment in nation-owned and private businesses. It has also forged joint ventures with Suncor and other resource extraction companies.

In 2021, Tsuut’ina Nation announced a $4.5 billion development project close to their already-running Grey Eagle Casino. Taza Park is planned as a mixed-use community which includes retail, residential, and entertainment space, featuring a 75,000-square-foot Metro Ford facility with 44 service bays, 13 electric vehicle charging stations, and a high-tech customer lounge. Tsawwassen First Nation, south of Vancouver B.C., is also a big player in land management, attracting Ivanhoe Cambridge Capital Corp. The community built one of Canada's largest malls, occupying 107 acres and housing 1.5 million square feet. Last year, the mall was sold to Central Walk, a Chinese development corporation. Tsawwassen First Nation is now working with GWL Realty to develop a 450,000-square-foot Amazon shipping warehouse.

In 2016, after a grueling 27-year Supreme Court battle, Canada and the Province of British Columbia recognized the Tsilhqot'in people's inherent territory by granting nearly 1,900 square kilometers — only 1/4 of the land the Tsilhqot'in people claimed — full Aboriginal Title and Rights. This precedent-setting decision now gives the Tsilhqot’in National Government the power to implement a tax fee, not only for high-end luxury outfitting resorts operating in our territory but also for residential homes. This is an automatic new revenue stream that will create further streams of revenue while the Tsilhqot’in Nation moves closer and closer to being a fully self-governing nation.

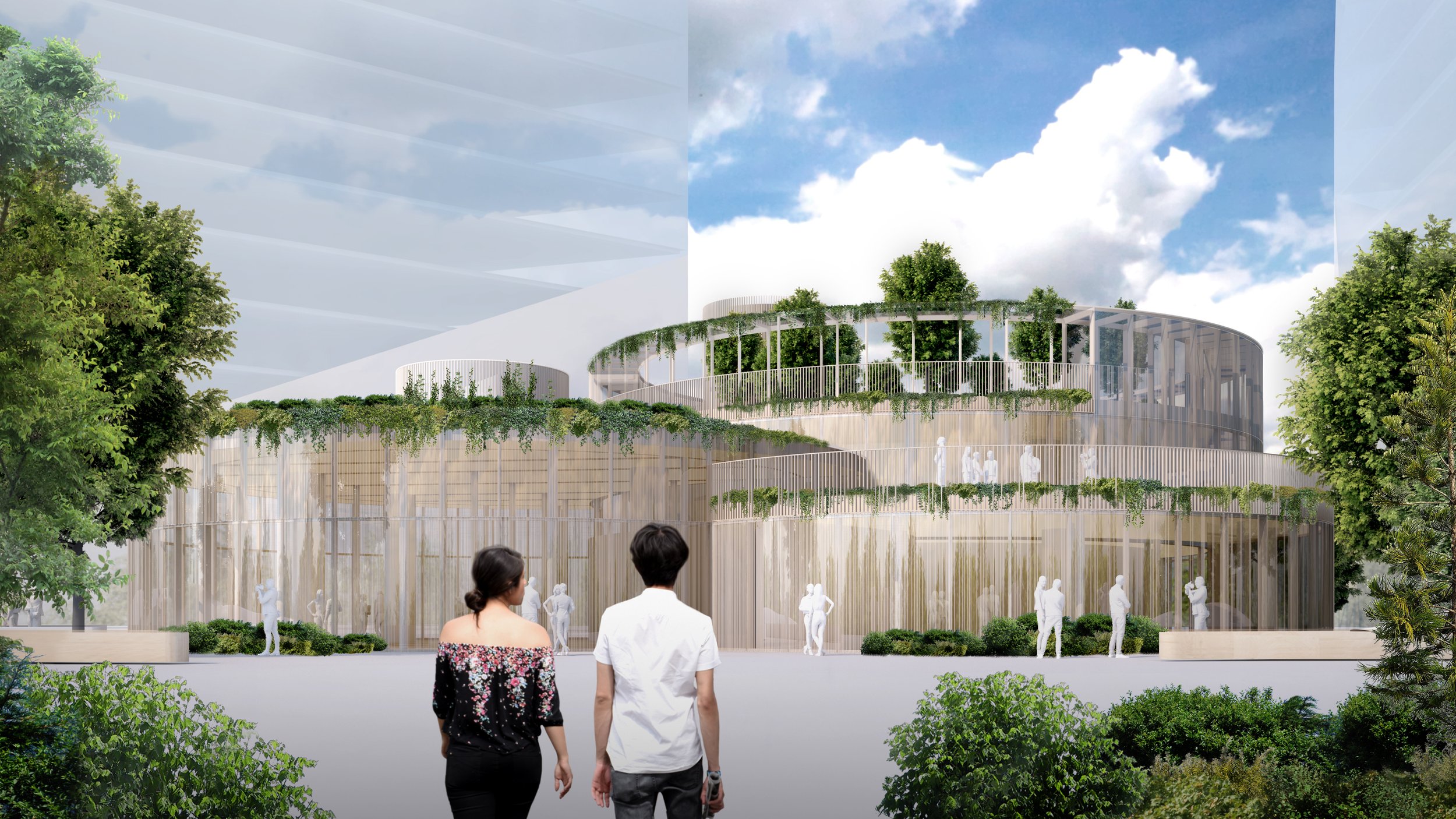

Squamish Nation, located in Vancouver, B.C., is arguably the richest and most financially influential Indigenous nation on the planet. Not only is it home to lush temperate mountain-rainforests and abundant land and ocean wildlife, but it also sits on one of the highest and fastest-growing real estate markets in the world. In 2019, the nation's economic development arm, 'Nch'ḵay̓', approved a $3 billion housing project called 'Senakw' that is expected to generate between $8 billion to $10 billion in revenue from rent and condo sales over the project's 120-year lifespan. Their new development proposal north of Vancouver is even bigger, spanning 350 acres across multiple sites in north and west Vancouver, and expected to generate revenue in excess of $20 billion.

The right thing to do is to acknowledge the level of opportunities and privileges many -- but not all -- First Nations communities have regarding education, health, clean water and air, and employment. The next step is to envision large-scale, world-changing projects that we as First Nations can create with the amount of influence we have. Helping our Indigenous cousins from Central and South America seems like a noble goal.

CHAPTER 3: SPATIAL vs. TEMPORAL

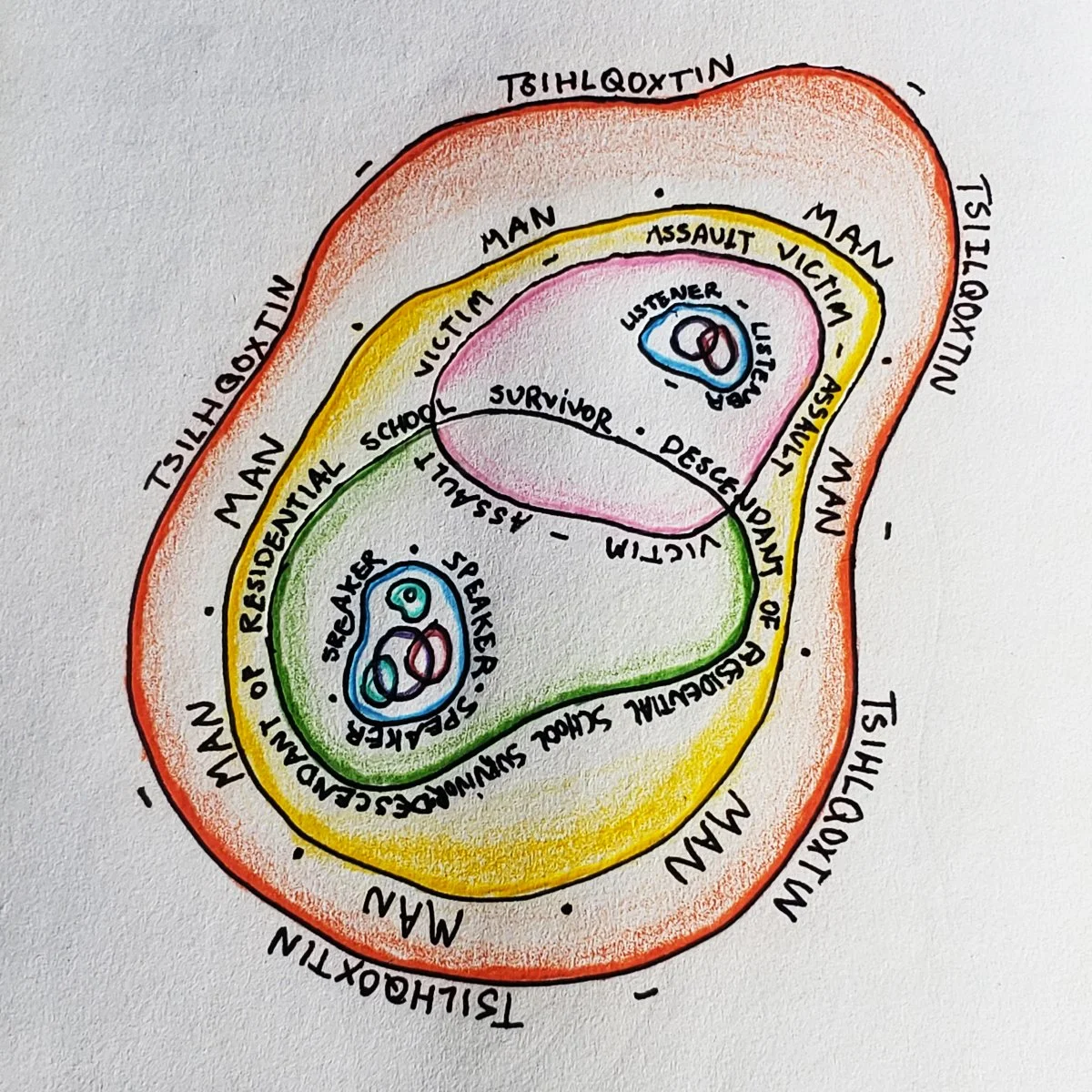

Spatial Identity

Imagine a cell structure. Picture the cell structure holding within it other structures. This is how we will illustrate our Absolute Identity Structure; an absolute identity is what holds all of our other identities within. An absolute identity is with what lens we are perceiving our external world with and with what filtration system we are synthesizing information as useful. As Ram Dass said, “when I was bald, I was viewing the world with a ‘bald and not-bald’ filter. I was comparing my baldness with everyone elses un-baldness.” Many people throughout the world are perceiving the outside world through internal struggles and past behaviour patterns. This becomes an identity of ours; identifying with our traumas or past experiences. A temporal identity may also include a town, a city, a nation, or a job. Many business people consider themselves as “person of business”, which of course, dictates how they perceive the world and actions they take towards the external world.

Temporal AIS (Absolute Identity Structure)

Because these temporal things are simply concepts, we are identifying with our own mind’s creation, and can then create more upon such foundation. Imagine if our absolute identity was made up of a temporal concept, and we will in the cell structure with other identities; “first and fore-most I am a Canadian, a Canadian lawyer, A Canadian lawyer and board member of the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, etc. etc. This means, if Canada somehow dissapears, the entire chain created pops; there can be no federal organization of lawyers because Canadian lawyers don’t exist anymore, and Canadian lawyers don’t exist anymore because Canada no longer exists. When our entire AIS pops, then our nervous system creates a constant state of hyper-arousal, and a never-ending loop of existential crises — we never know who we are.

However, as you can imagine, an AIS with a spatial identity as the foundation is much harder to simply pop away. Tŝilhqot’in is a collective identity different than an identity such as a town, state, nation, occupation, sports team, or time in history. In my language, Tŝilhqot’in translates directly as “Tŝi” meaning ‘rock’, “Lhut” meaning ‘glacier’, “cox” as ‘river’, and '“t’in” as ‘people of’; ‘People of the Glacier-Rock River’. This means my individual and communal AIS is an actual physical, and more importantly, natural occurring phenomena of the world. We as Tŝilhqot’in can hold the water, drink from it, and interact with it in many other ways. This is impossible with conceptual creations of the mind.

Spatial AIS

This means that we now have a more secure structure to place our other identities within; such as ‘filmmaker’, ‘lawyer’, ‘women’s group volunteer’, ‘chief’, ‘student’, etc. Our occupations and group memberships can change throughout our life, but that doesn’t create such an existential crises, because our absolute identity still exists, and ceremonies have been created to honour such identity.

Looking forward into this planetary transition of consciousness around our place on earth and in the cosmos, who do we want stewarding the waters of change? The same temporal societies and institutions, utilizing the hubrus of their minds to think our way out of the mess they have created? Or do we jump into the great uncertainty of giving the last remaining spatially-identified societies on the planet the benefit of the doubt to lead us out of this mess? What structures can we learn from as new intentional communities are being made all throughout Costa Rica, Mexico, Colombia, Brasil, and the Philippines? Perhaps adopting a new spatial identity — or learning from already existing ones — and nurturing that relationship, based upon the indigenous structures of AIS, can create generational waves of impact that will can wash away all of the junk that our collective minds have created over the centuries.

Communicating the importance of spatially-identified indigenous governance at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (April 2023)

World Indigenous Spiritual Biosphere Areas

(WISBA)

HOW IT CAN LOOK

After initial cultural exchanges brought together psychedelic plant medicine-using cultures of the Huichole, Shuar, Quechua, Piaroa, and Shipibo with the wealthiest First Nations communities in Canada, the leaders mutually saw the reciprocal benefits and potential of their exchanges; indigenous First Nations in Canada contextualized the gift of psychedelic plant medicines with their long-standing traditional ceremonies for the use of healing and deepened communal connections. During these trips, the local First Nations community toured their guests to the glacial mountains, clean watersheds, community centres, governance offices, and sacred places. The visiting youth began learning English and the local language. In the south, the hosting community welcomed a group seeking solace from the dark, cold winter climate of Canada. The First Nations youth, some of whom were on the verge of committing suicide spurred by the seasonal depression, got to now experience the warm blanket of the Sun, the ever-growing life of the jungle, and a culture still steeped in strong traditional plant medicine practices. The First Nations governance saw that they could formally adopt children, by their own traditions, and by the current Status Card system to share the many benefits Status Card holders possess in Canada; optometry, dentistry, and post-secondary education support. After years of collaboration between the communities and nations, their youth began to fall in love, and new babies were born. The first in a new generation of dedicated and devoted intention to create inter-generational alliances to protect and conserve the last remaining spatially-identified societies and the land they steward.

During this process, the First Nations governance created Conservation Departments within their governance structure. These new projects collaborated with other newly created positions across First Nations governments in Canada. They created a WISBA Trust where some of their government corporation revenue could be donated into. A council, perhaps called the ‘Council of Conservation’ was created to oversee how the funding was used to purchase land internationally, for the purpose of protection, conservation, restoration, and cultural revitalization. A nation-to-nation dialogue without the need of a middle-man institution.

A First Nations tribal school in British Columbia offers curriculum based on their nation’s cultural revitalization plan. But something new is happening at this school: they have created a new international indigenous education course. These curriculums will include monthly in-person presentations by medicine people from the Maya jungle of Belize, musicians from an all-Quechua school in Sacred Valley of Peru, Shipibo ceremonialists from the Amazon Basin, Huichole artists from the tropical desert of Mexico, or founders and knowledge keepers of the ‘Kawsak Sacha’ Living Forest Declaration by the Sarayaku people of Ecuador.

In the same school, the international indigenous curriculum will offer travel opportunities to exemplary students to visit the protected areas their nation helped secure and protect. These visits were specifically planned for various different cultural, political, and scientific reasons. For example, while reforesting a jungle, a class of aspiring biologists learned about the communication networks of a rainforest in relation to their own forests back home. Women artists from each community shared knowledge about beading and textiles with each other, and groups of youths participated in various fertility ceremonies, which eventually led to new families being created — a true nation-to-nation alliance.

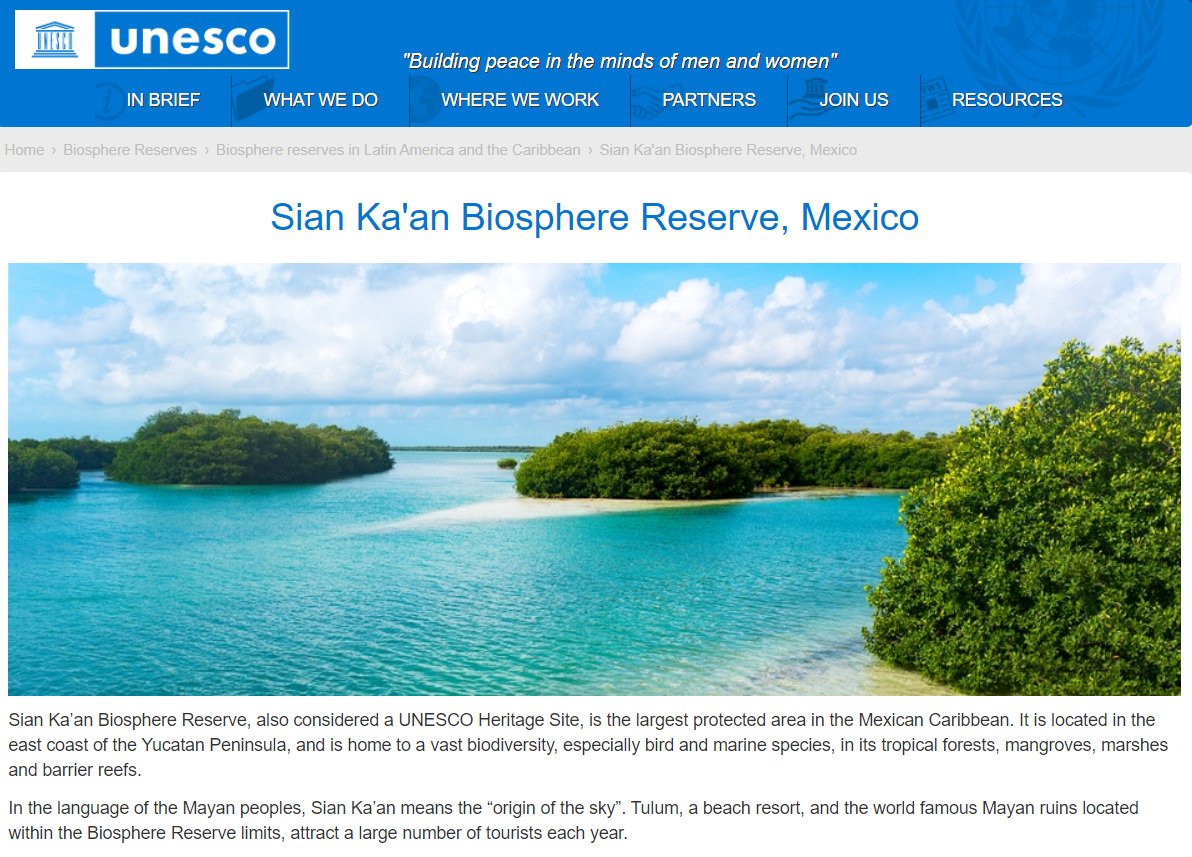

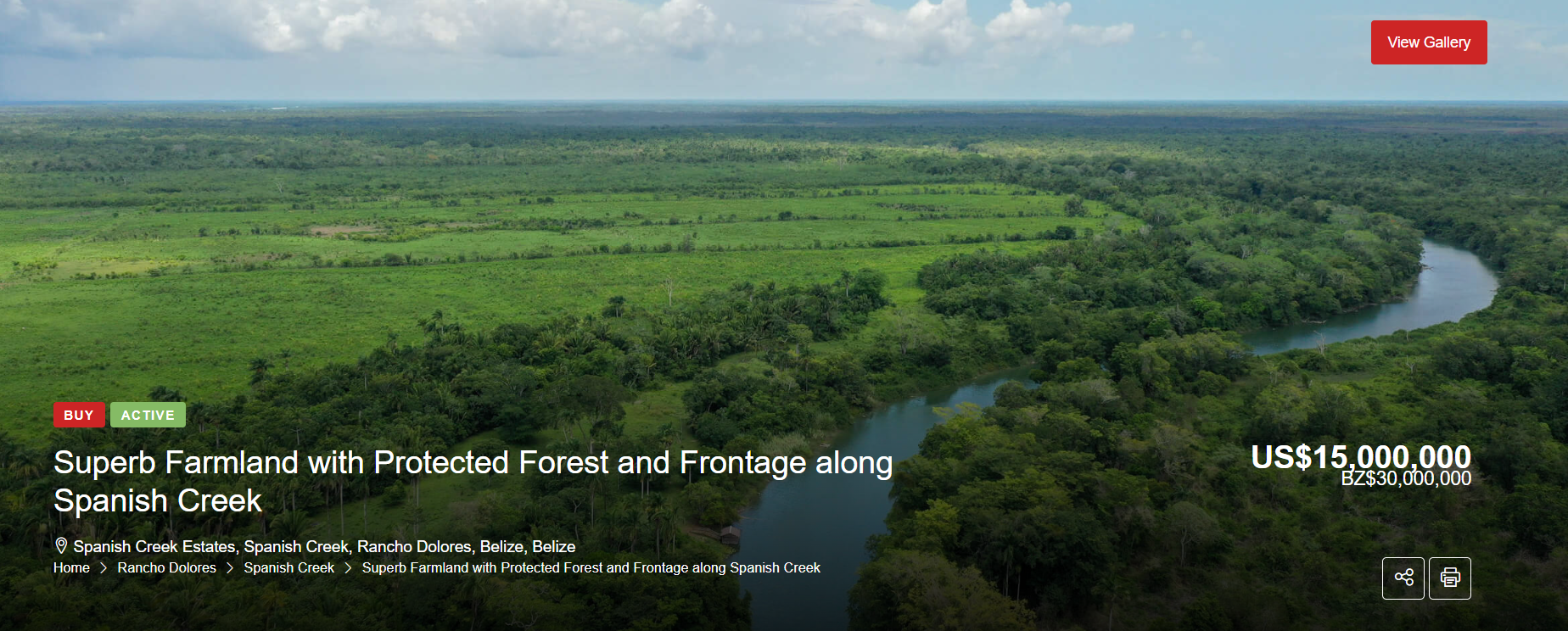

As of the writing of this essay, the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO Heritage site, is currently for sale for $49 million USD. This is worth repeating: a UNESCO-acknowledged, federally enacted conservation area on the Yucatan Caribbean coast of Mexico is for sale. Another example is in Belize, where a 5,243-acre farmland and protected forest is currently for sale for $15 million USD. This private title ownership provides another layer of security when creating a consortium of World Indigenous Spiritual Biosphere Areas — and a glaring example of how a UNESCO acknowledgement is not enough to protect such areas.

Digital Nomads, Mennonite farmers, and Global Investors are all setting foot on the final frontier of our planet; the last remaining pristine biospheres of Central and South America. Each of whom seem to have the best-intentions at-heart, however whose narrative shall we rely on to tackle the problems the current system has created? Perhaps it is the last-remaining spatially-identified societies on the planet who should have both cultural and economic stewardship of the world’s next steps into symbiosis with Nexwenen (our land - Tsilhqot’in), Nunavut (our land - Inuktitut), Allpanchik (our land - Quechua), tums na giǰɛ (our land - Homalco).

The future of traditional Indigenous culture and the last remaining pristine biospheres on the planet is at stake.

The international potential of wealthy First Nations and their economic development departments in Canada is now boundless. Their efforts to acquire large tracts of private land in Central and South America will help protect and conserve the last remaining vestiges of Indigenous cultures and the pristine biospheres from which they derive their wisdom.

Through the combined leadership and vision of billion-dollar First Nations governments and small land-working communities, Indigenous peoples can demonstrate to the world the vital role they play in safeguarding the environment and building sustainable economies for future generations. No more waiting for the rest of the world to act on behalf of Indigenous peoples.

The co-creation of World Indigenous Spiritual Biosphere Areas (WISBAs) represents a proactive measure towards securing a future where Indigenous peoples have more control over the financial, administrative, and cultural narratives of our world, rather than risking colonization by others—again.

What is a WISBA?

WISBA stands for World Indigenous Spiritual Biosphere Area. WISBAs are a new “classification” of globally protected land and waters that are solely governed by the nation-to-nation collaboration of indigenous First Nations governments and localized indigenous communities in Central and South America -- no bureaucratic, institutional middle-men to create unnecessarily complicated systems of governance and acknowledgement.

How are WISBAs created?

The collaborative efforts between the Council of Conservation, made up of newly created Conservation Department heads within First Nations governments and localized indigenous communities within Central and South American countries, will utilize funds from the WISBA Trust to purchase large tracts of land for the sole purpose of protection, conservation, and cultural revitalization.

How will land be acquired?

A WISBA Trust will be created, to where each of the partner indigenous First Nations governments will donate into, through revenue from their corporations. The Council of Conservation will decide, after lengthy collaboration with all involved parties, to foresee a private land title purchase – the same process organizations such as the Nature Conservancy and other private organizations can purchase land for conservation.

How is this different than UNESCO Biosphere Areas?

UNESCO Biosphere Areas are only granted with the acceptance of the ruling government. This land can still be “Crown Land”, Federal land, or lands that don’t fall onto protection or conservation class within the “ruling” nation. As the example stated, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Yucatan state of Mexico is for sale for $49 million USD.

WISBAs used as Carbon Credits

If chosen to adopt, the revenue created from the carbon credit offsetting program can not only go back into the WISBA Trust for further use in gathering land for protection and conservation, but it can go towards the funding of cultural exchange projects within the WISBA territories.

Why would WISBA use Carbon Credits?

If chosen to utilize, the spatially-identified Fist Nations governments and indigenous communities can gain international economic footholds, and thus have a more equal say in world climate change and conservation discussions.

How will these cultural exchange projects be decided?

A Council of Culture will be created to steward funding towards projects that are aligned with the agreements laid out by the Council of Conservation and the involved parties for each WISBA.

How is this different from the ‘Amazon Sacred Headwaters Initiative’?

The ASHI, started in 2017, is a collaborative effort between various indigenous-led organizations and non-indigenous organizations. The WISBA vision is solely indigenous-led. Both projects have different objectives; the ASHI is focused on influencing policy discussions at world conferences as well as looking for investors, whereas the WISBA initiative is focused on the immediate purchase of land and international indigenous cultural exchange projects that take place on said land.

How can non-indigenous people help?

Specifically in regards to WISBA, knowledge of trust law, property law, and charity laws will all be relevant to the objective.

Helping bring together indigenous cultural representatives, in non-formal, on-the-land exchanges will be vital for the success of this project. This means, learning from local indigenous communities, helping serve their needs, and adopting a relevant individual and communal spatial identity can all lead to successful co-creations for the future our next generations.